Reading Lainey Feingold's (2021) "Structured Negotiation: A Winning Alternative to Lawsuits" - 2nd Edition (Cont'd)

Stage 2: Establishing Ground Rules- Ch. 6: Initial Response and Structured Negotiation Ground Rules

This week, my reading of Lainey Feingold’s Structured Negotiation: A Winning Alternative to Lawsuits (2nd ed., 2021) has brought me into more technical territory as I move into Stage 2 of the process: Establishing Ground Rules and tackle Chapter 6.

Chapter 6 covers three practical and strategic elements:

how to evaluate a response to the opening letter,

how to structure an effective ground rules agreement, and

how to convince a would-be defendant (or, in our context, a responder) to sign that agreement.

This structure offers a reminder: no matter how compelling we believe our opening letter may be - and here we must be careful not to become too easily convinced by our own arguments -Structured Negotiation is never a certainty. It requires ongoing care and commitment to bring participants fully into the process.

Feingold writes from the standpoint of a lawyer acting on behalf of a client with a claim that could support a viable lawsuit. That’s a very different premise from many of the matters we see in our Veterans’ ADR Program, where the need may be to address a moral injury or unacknowledged harm, rather than a claim with a clear pathway to judicial remedy.

Often, the “negotiation” - if we can even call it that - is not about reviewing a past decision but about engaging a discretion that has yet to be exercised, in the hope of avoiding a future decision that might entrench unfairness or necessitate review.

So, as I read Chapter 6, one key question kept emerging:

Could Structured Negotiation work as a model for collaboration - or, more ambitiously, co-production - with a government or administrative entity that is being invited to exercise discretion? What fine-tuning might that require?

After reflecting on the chapter and sketching a draft Ground Rules document, I believe it can. Structured Negotiation has much to offer in this space, especially when we pay care-full attention to the relational architecture of the Ground Rules.

That includes not only what we ask of the responder, but also what is asked of the claimant - in this case, the veteran. This reciprocity is at the heart of a values-based, trust-building process.

In this Field Note, I’ll explore what that fine-tuning might look like and explain my sources of support.

It only takes the slimmest of openings

Chapter 6 begins with evaluating the response to the opening letter and a reminder:

Do not expect the recipient of an opening letter to rush with open arms to embrace Structured Negotiation.

However, there is also encouragement and a call for persistence:

...an effort to engage in Structured Negotiation should not be abandoned simply because a response is not received on a given date, or a delivered response is considered inadequate.

Two short passages reveal that the key might be found in understanding and honouring relational underpinnings of Structured Negotiation:

Structured negotiation works because we do not assume the worst. We do not take a non-response personally and we give potential negotiating partners the benefit of the doubt.

and:

Only the slimmest of openings to discuss the process is required.

That “slim opening” might be no more than a guarded willingness to meet and discuss. If you get that, it is enough. From there, you can get on the phone and introduce your draft Ground Rules document, explaining “its purpose and value to the potential negotiating partners.” Once you’ve done that, you can send a draft.

Elements of the Ground Rules Document

One of the benefits of preparing a Ground Rules document is that it provides an opportunity to demonstrate that:

... while claimants prefer not to file a lawsuit, they expect the same relief as is available in an adversarial process.

“The same relief”?

In our Veterans’ ADR setting, whilst it is often possible to do that, there will be cases where there is no clear pathway to (legal) “relief” or remedy. In those cases, we need to take care to describe the redress we are seeking – often as a floated possibility. What we are doing, in those cases, is prompting the exercise of moral imagination – bringing to light the possibility that something better than the present state of affairs is attainable through patience and perseverance. Our Ground Rules document, therefore, needs to provide the framework within which the participants can practise that patience and perseverance.

Let’s have a look at what Lainey Feingold identifies as the necessary elements of that framework.

1. Identify claimants and counsel

In Structured Negotiation, a Ground Rules document is always a contract. One needs to identify the correct parties and the entity that may be sued if the negotiation does not lead to resolution.

In a structured collaboration with a government or administrative entity, that might not always be possible. The responder may be reluctant to bind the exercise of a discretion. The exercise of that discretion might not even be amenable to legal challenge. Ultimate decision makers may be somebody in a different department, a Minister, or even Cabinet. Nevertheless, the Ground Rules document can still identify the participants and set out their understanding of what will happen and, equally importantly, how it will happen. That brings us to the second element.

2. State the purpose of the negotiation

This was an element which, in our Veterans’ ADR context required a lot of care. Feingold explains:

A typical “purpose” statement includes open ended paragraphs such as the following:

- to protect the interests of all parties during the pendency of negotiations concerning disputed claims regarding [insert brief description of issue];

- to provide an alternative to litigation in the form of good faith negotiations concerning disputed claims about [insert same description]; and

- to explore whether the parties disputes concerning [insert same description] can be resolved without the need for litigation.

I’ve highlighted the verbs because they show that the Ground Rules document sets an active framework within the negotiation can occur.

“… alternative to litigation…”

Whilst litigation will often be he perceived alternative, in a structured administrative collaboration, “litigation” might not always be the best or most accurate expression. The complexity of administrative proceedings might require a more specific description of the type of litigation that is contemplated o for example, the purpose could be stated as the need “to avoid merits or judicial review”; or, more positively, “to reach a fair (first instance) decision that all participants can accept.”

Beyond litigation, however, many claims involving government entities play out in the social and political domain. This raised a further question for me about whether Structured Negotiation could be viewed as an alternative only to litigation, or might it be effective as an alternative to other forms of advocacy especially when government entities were involved. Could it, for example, also be an alternative to activism – or, if not an alternative, could the Ground Rules document acknowledge expectations about how activism and negotiation will interact by outlining a shared understanding of how advocacy efforts will be handled during the process?

I was thinking of the similarities with good faith industrial bargaining. Might there be benefit in expressly preserving the right to engage in social or political activism in support of a claim; and if parallel activism was not considered by one party to be “in good faith” could there be a circuit breaker to bring the parties back to collaborative negotiation? Might it set a frame for both parties?

These are questions that reflect what is often the reality of the contest in a structured collaboration with a government entity, where what takes place in the political or social domain may carry more weight than what occurs in the legal domain. Ultimately, they are questions that go to trust and safety, or assurance, and for that reason there may be value in including them in the Ground Rules document.

This brings us to a new dimension. While a purpose statement framed in terms such as “to protect,” “to provide,” or “to explore” appears to express the objective purpose of the Ground Rules document, especially in relation to avoiding litigation, might there also be - particularly in our Veterans ADR context - a relational purpose? Such a purpose would connect the process to an ethic of care and to deeper commitments including empathy, respect, and the restoration of trust.

The relational purpose

This distinction between objective and relational purpose has helped me rethink how a Ground Rules document might function in structured collaboration settings, especially in our Veterans’ ADR work.

The objective purpose remains important. It sets out what we are here to do - protect interests, avoid escalation, and explore resolution. But the relational purpose runs alongside it. It expresses how we want to do this work - with integrity, openness, trust, and care.

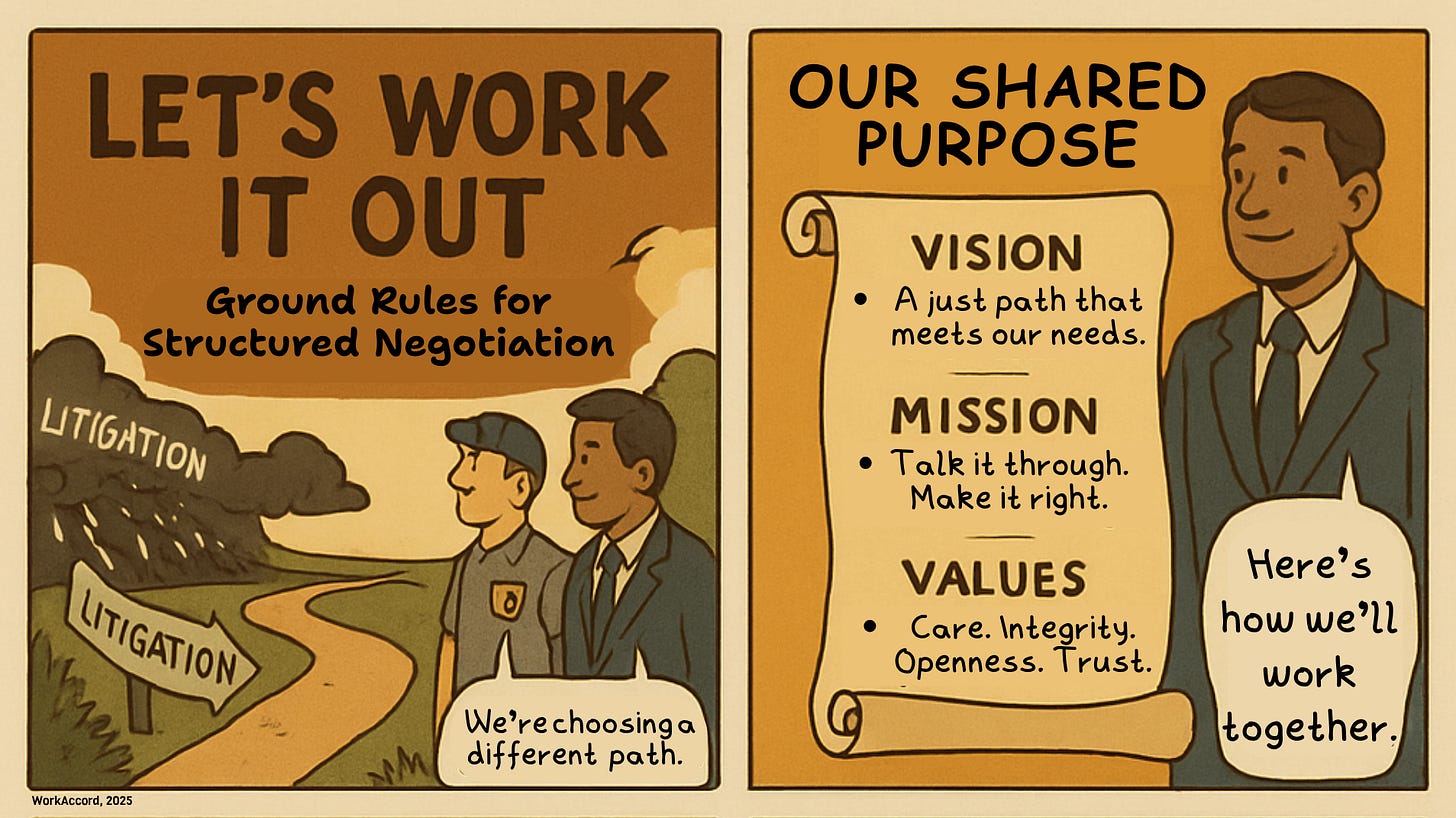

To bring this idea of relational purpose to life, I drew from the approaches of J. Kim Wright’s Conscious Contracts and Linda Alvarez’s (2016) Discovering Agreement and began experimenting with a visual format. The result was a set of comic book panels - two so far - that helped me imagine what was happening in the process, beyond what could be captured in words alone. I found that the act of creating the panels made the relational dimension of the Ground Rules more tangible.

Here’s how it turned out.

What I’m discovering is that this isn’t just about creating a template for an agreement - it’s about storytelling, integration, and relational design. I’m needing to ask:

How can we tell a story about collaboration - one that’s values-based, trauma-aware, hopeful, and intentional?

In this example, the imagery clarified a shift away from litigation, while the condensed language in the scroll - vision, mission, and values - helped me to articulate what we were choosing instead. Strangely enough, it was the words that took the longest to refine. They had to carry ethical weight without legal baggage and feel invitational rather than contractual. Of course, I had some help from ChatGPT with the artwork, since I’m no artist - but the process felt integrative and creative, and most importantly, it allowed me to hold together the legal, relational, and imaginative dimensions of the Ground Rules in a way that felt both grounded and hopeful.

In taking this aspect of the work forward, I’d be hoping to connect with a cartoonist, who might specialise in creating comic-book contracts. But, for now, I hope this will give you some idea of the direction this work might take.

In the next section, I return to the elements of the Ground Rules document, dealing with the topics to be negotiated.

1. List the topics to be negotiated

Topics may vary from negotiation to negotiation. However, the core suggestion, which Feingold offers is to:

... Include subjects, but not specific outcomes. Identifying issues for the ground rules document is not taking a position; It is agreeing to a discussion. [Example] “improving and maintaining accessibility for individuals with visual impairments to the companies prescription information”; “training of appropriate personnel and adoption of appropriate policies.”

Mediators would recognise the wisdom in that. It is about naming the topics that matter – those about which the participants need to have a serious conversation on their way to finding a solution, even if those topics do not form part of the solution.

In the Veterans’ ADR setting, this approach is especially important because some topics carry emotional weight or moral complexity even when they lie outside the scope of formal remedies. Naming these topics and treating them with care affirms that they matter, even if the eventual resolution takes a different path.

2. Toll the statute of limitations

In our Australian context, we might explain this in terms of putting any statutory or other lime limits “on hold” to allow the participants time to conduct their negotiation without being hurried to commence legal proceedings.

That participants can do that, contractually, was affirmed by the High Court recently in Price v Spoor [2021] HCA 20, where a mortgagor agreed that, in any future proceedings, it would not rely on statutory lime limits. However, this might not apply as a general rule to all limitation periods and similar restrictions on when a party can commence a legal claim.

From a relational perspective, tolling offers more than just procedural flexibility. It reflects a shared willingness to slow the pace, to prioritise mutual understanding over procedural advantage, and to allow space for trust to develop before resorting to legal action.

However, if time may be running against you, be sure to get professional advice from a practising lawyer.

3. Protect the confidentiality of shared information

Feingold suggests that the Ground Rules document should protect the confidentiality of “information discussed or exchanged during the negotiation.” This creates a safe environment where participants can share what they know, think, or feel without concern that it will later be used against them.

On the matter of dealing with evidence, Feingold adds:

There is no “gotcha” in Structured Negotiation so there is no need to hide [or destroy] evidence that may prove or disprove a claim or defence. We never even use the term “evidence” because our focus is on information that helps participants resolve claims, not prove or disprove them.

In our Veterans’ ADR context, this distinction is especially important. Many participants carry painful histories or complex case narratives that are difficult to express in the language of admissible evidence. Protecting the confidentiality of what is shared allows the process to focus on understanding and relational repair, rather than legal positioning in anticipation of a lawsuit somewhere down the track.

4. Do not require an admission of liability

This element actually goes beyond merely choosing not to require an admission of liability. Feingold suggests that the Ground Rules document should expressly state that liability is not admitted. She explains:

A Structured Negotiation ground rules document includes a non-admission of liability clause for the same reason there is a confidentiality provision. Both sections allow the type of honest conversation that is not possible if negotiating partners are worried that participation may hurt them later. We use standard language

“the parties recognise and agree that entering into this agreement does not in any way constitute an admission of liability or any wrongdoing by any party, and that all discussions and negotiations pursuant to this agreement will constitute conduct made in an effort to compromise claims …

In our Veteran’s ADR programme, we might not speak in terms of “compromising claims”, but rather in terms of “reaching an outcome that all participants are able to accept as fair.” That is because, as we have previously observed, there may be no actionable claim that is capable of being “compromised; and, even when there is, the full injury that is to be addressed might not be able to be reduced to a compromised claim.

In this context, the standard non-admission clause still serves an important purpose. It reassures the responder that participation in the process will not be taken as an acknowledgment of wrongdoing. At the same time, it preserves space for the veteran to speak openly about harm, experience, and redress - without having to force that experience into a liability framework. In this way, the clause supports both safety and honesty, for all participants.

5. Preserve rights and a fee shifting statutes

The practice that the unsuccessful party in litigation should pay the legal costs of the successful party (or at least some of them) is more common in Australia than it is in the U.S.A. Accordingly, Feingold suggests to her American readers – and those from jurisdictions where similar rules apply that:

When Structured Negotiation is used to resolve claims under fee shifting statutes, this paragraph in the ground rules document protects the right of claimants and lawyers to obtain fees from negotiating partners: [sample clause then given].

Even so, there would be benefit in including something similar in an Australian Ground Rules document, especially if legal costs are not recoverable – either because legislation provides that the parties ought to bear their own costs (as occurs in some tribunals); or because there is no present “claim” that attracts a liability to pay costs even if unsuccessful.

In those circumstances, it may be helpful to set out how legal costs may be paid – as between the participants. In the interests of transparency, it may also be worthwhile to set out how costs are being funded – especially where rules about champerty and maintenance (the practice of a “stranger” without a proper interest paying legal costs to support a claim) apply.

In a relational process such as Structured Negotiation, clarity about costs is not just a procedural matter. It also supports trust and transparency, especially when parties come to the table with differing levels of access to support or resources.

However, where legal costs may be an issue, be sure to get professional advice from a practising lawyer.

6. Identify an effective date and provide for termination of the agreement

The final element in the Ground Rules document is the inclusion of a start and end date. The end date may be a fixed date, which serves to keep the participants focussed, or it may be a date following notice. However, this wise advice is added:

Parties should include a set expiration date in the ground rules document with caution. Invariably resolution takes longer than anticipated. A specified termination date can create unreasonable expectations among clients and counsel.

In structured collaboration settings, it may also be helpful to signal how the agreement might be reviewed or refreshed over time, especially where trust is still being built. Termination clauses can be written not just as exit strategies, but as moments for pause, reflection, or reset.

Having outlined the eight elements of the Ground Rules document, Feingold then turns her readers’ attention to the topic of convincing responders to sign the agreement.

Checklist for convincing would-be defendants to sign the document

Chapter 6 closes with four strategies for convincing responders to sign the document.

1. Share names of previous negotiating partners

The purpose in sharing names and providing references is to provide reliable assurances from third parties in order to “assuage fears about the method”. If you have satisfactorily concluded a Structured Negotiation, it will have been helpful to have asked your negotiating partners if you can nominate them as process referees in future matters.

However, if you are new to the process, or do not have someone whom you can nominate as a process referee, it would always be possible to reference the book or even Lainey Feingold’s website – as you may have done in your opening letter. Possibly someone who is familiar with the process – even if you have not had direct dealings with them – might be prepared to offer support as a “process referee”.

2. Allay fears of lawsuits from others

In this regard, Feingold notes that “potential negotiating partners often ask whether signing the Structured Negotiation Agreement will protect them from being sued by third parties about issues in the negotiation.” That fear can sometimes result in the responder’s seeking to wrap the whole process in secrecy. However, this may be counterproductive. Whilst Feingold explains that one can never give any guarantees, her observations, based on experience, are encouraging. She writes:

Being able to share Structured Negotiation progress limits the possibility of outside lawsuits by making others aware that the alternative dispute resolution process has been initiated.

This is a solid endorsement of the importance of openness in a process where the safeguards are intentionally designed into the structure. She adds:

Regardless of whether the ground rules document is public, the possibility that a lawsuit may be filed is not a reason to reject Structured Negotiation.

... Even if someone else does file a case, resolving a claim in Structured Negotiation is still more cost effective and less time consuming than litigation. Saying no to Structured Negotiation because of a future uncertainty is not prudent.

3. Emphasize that Structured Negotiation is cost-effective and fair

Of this, there should be little doubt – provided that some substance can be given to the concept of what is “fair”.

Again, structure and frameworks can help. In our Veterans’ ADR programme, we have focussed on developing a concept of relational justice that is now informed by insights from the Fairness Triangle and offered – in outline at least – in our opening letter. This way, our responders can be clear about what we are proposing and can check if it is aligned with their own principles and codes of conduct or values.

4. Calm concerns about money settlement amounts

Often there will be an interest in obtaining a monetary settlement or compensation, and whilst it’s never “only about the money”, it is important that discussions about money do not hijack the negotiation, for as Feingold notes:

Lawyers do not like uncertainty. When faced with a ground rules document referencing damages payments and attorneys’ fees, the natural inclination is to ask “how much?”

“Money negotiation”, she observes, “is the most traditional and often difficult, aspect of Structured Negotiation.”

One thought we have been developing in our Veterans’ ADR programme is that whilst it is important to name the money issue squarely and lay it on the table, it might be better not to make the payment of money the chief focus. Not to make payment, of itself, the right thing to do; but, rather, to let the payment of money flow naturally from identifying the right thing to do - addressing the cause of the harm to be redressed.

This seems consistent with suggestions made by Feingold in Chapter 5 concerning the framing of the opening letter. By all means describe the type of redress sought but do not state a position or make a demand because, at this point, we are still at the stage where we “should avoid a demand mentality and instead focus on an invitation mindset.”

These four strategies do not guarantee agreement, but they help build the conditions for trust. At their heart, they reinforce what Structured Negotiation requires from the outset: an open door, a willingness to listen, and a shared belief that something better can be built together.

References

Linda Alvarez. Discovering Agreement : Contracts That Turn Conflict into Creativity. American Bar Association; 2016.

Lainey Feingold (2021) Structured Negotiation: A Winning Alternative to Lawsuits, Second Edition. A11y Books. Kindle Edition.

Sharon Pratchler, K.C., Ombudsman Sasketchewan (2023) Annual Report, pp. 7-8. - description of the Fairness Triangle https://ombudsman.sk.ca/app/uploads/2024/04/2023-Omb-Annual-Report.pdf

J. Kim Wright, Conscious Contracts: Bringing Purpose and VAlues into Legal Documents https://jkimwright.com/conscious-contracts-bringing-purpose-and-values-into-legal-documents/