Reading Lainey Feingold's (2021) "Structured Negotiation: A Winning Alternative to Lawsuits" - 2nd Edition (Cont'd)

CHAPTER 5: WRITE AN INVITATION TO NEGOTIATE

Something happened this week

There is a power in the Universe, I believe, that every now and then nudges us forward – sometimes none too gently! That says to us, “You’d better get a move on,” and sends us a challenge that prompts us to do just that. And the challenge is irresistible. But somehow the grace and the means to meet that challenge are also given to us. And – if we approach it with perhaps more hope and trust than we’re accustomed to – we just might meet that challenge.

Something like that happened to me this week. I’d been plodding along comfortably with my weekly chapter reviews of Lainey Feingold’s Structured Negotiation: A winning Alternative to Lawsuits – 2nd edition, when I was asked to help with the draft of a letter inviting a public sector entity to participate in a collaborative process for finding a solution to a wicked problem that was affecting a veteran’s entitlements – and more than that, the veteran’s quality of life and needs for, recognition, autonomy, belonging, security, and meaning. These needs are not traded in negotiation - they are honoured in relationship and are essential to any concept of relational fairness.

Of hope ...

Now, four weeks of chapter reviews was hardly sufficient preparation to undertake that task! But, as the Universe would have it, I had been working on this type of wicked problem consistently for several months; and, fortunately, I had previously read Lainey’s first edition of Structured Negotiation, which had helped me to design a Structured Negotiation process for handling professional conduct grievances that had been raised with an industry peak body. We had successfully implemented that process in more than 50 grievance interventions in the course of which I had gained some experience in preparing opening letters on a pathway, which we had called “Structured Listening” – a type of facilitated information exchange in which a responder to a professional conduct grievance was invited to participate in identifying the right thing to and then encouraged to do it.

Nevertheless, the request hurried me on and placed my review of Lainey’s Chapter 5: Write an Invitation to Negotiate in a new and challenging context. So, I had some hope that I might be able to meet the requirements of task given to me.

Of grace ...

Now, did I also mention “grace” in my introduction, earlier? This was the astonishing thing. I had written, a month or two earlier, about fairness in our Veteran’s ADR programme in consequence of which I had been introduced to “The Fairness Triangle” and criteria for its implementation by Sharon H. Pratchler, K.C. – its distinguished promoter, Ombudsman & Public Interest Disclosure Commissioner for the Canadian Province of Saskatchewan. We had got chatting and I was excited to find that the Fairness Triangle – with its emphasis on procedural, substantive and relational fairness – had been widely adopted across the public and university sectors in North America.

The Fairness Triangle and the means for operationalising it as a lens through which participants in a collaborative process might be encouraged to “identify the right thing to do and then encouraged to do it” gave real substance to what Lainey Feingold calls the “Gut Issue” about which she writes:

If possible, wrap claimants’ experience in a gut-issue like privacy, security, safety, or fairness.

There it was - the piece I needed in order to elevate my opening letter from one that merely presented an unhappy story of grievance to one that presented a solvable problem and a structured framework and approach for dealing with it. After a quick check with Sharon, who graciously permitted me to reference the Fairness Triangle process, I was ready to tackle Chapter 5 of Structured Negotiation whilst simultaneously implementing what I was learning from it.

I wanted to share that background, because it has shaped how I approached Chapter 5. It placed a hard edge on my reading, challenging me to think through the nuances of an opening letter which would not present a “claim” that could be litigated; but instead would need to present a case for the exercise of statutory and non-statutory ministerial discretions – including redress under an Act-of-Grace scheme, which might (if not exercised in favour of the veteran) be amenable to judicial review. It also shaped how I will approach this chapter summary and review – not so much by presenting a synopsis of the chapter as by suggesting how you might read it and what you might do with it.

Reading Chapter 5: Write an Invitation to Negotiate

Perhaps the best way read Chapter 5 is to read and write at the same time. If you have a matter in which you might be thinking about using Structured Negotiation, use it as your test case. If you don’t have a current matter, make one up - or use the scenario described in the Engagement section below.

Before jumping into the how-to sections of Chapter 5, I found it helpful to reflect on what Lainey has written about purpose and tone.

A structured negotiation opening letter seeks participation in a process. The reader is not asked to implement a particular policy at a given time or agree to pay a specified amount of money. No action, except a response to the letter, is expected … instead, the reader is invited to say “yes” to structured negotiation.

An opening letter is not a complaint.

Opening letters should avoid a demand mentality and focus instead on an invitation mindset.

This is so far removed from the letters of demand which I drafted in the course of over three decades of commercial litigation practice that it amazes me every time I read it – even though I now know it works.

The key to its success perhaps lies in her insight that:

A court complaint opens a doorway to conventional, confrontational, and expensive implements of dispute resolution. An opening letter is the first exposure a would be defendant has to another possibility.

The structured negotiation letter can, in many ways, be more effective for explaining a problem than complaint.

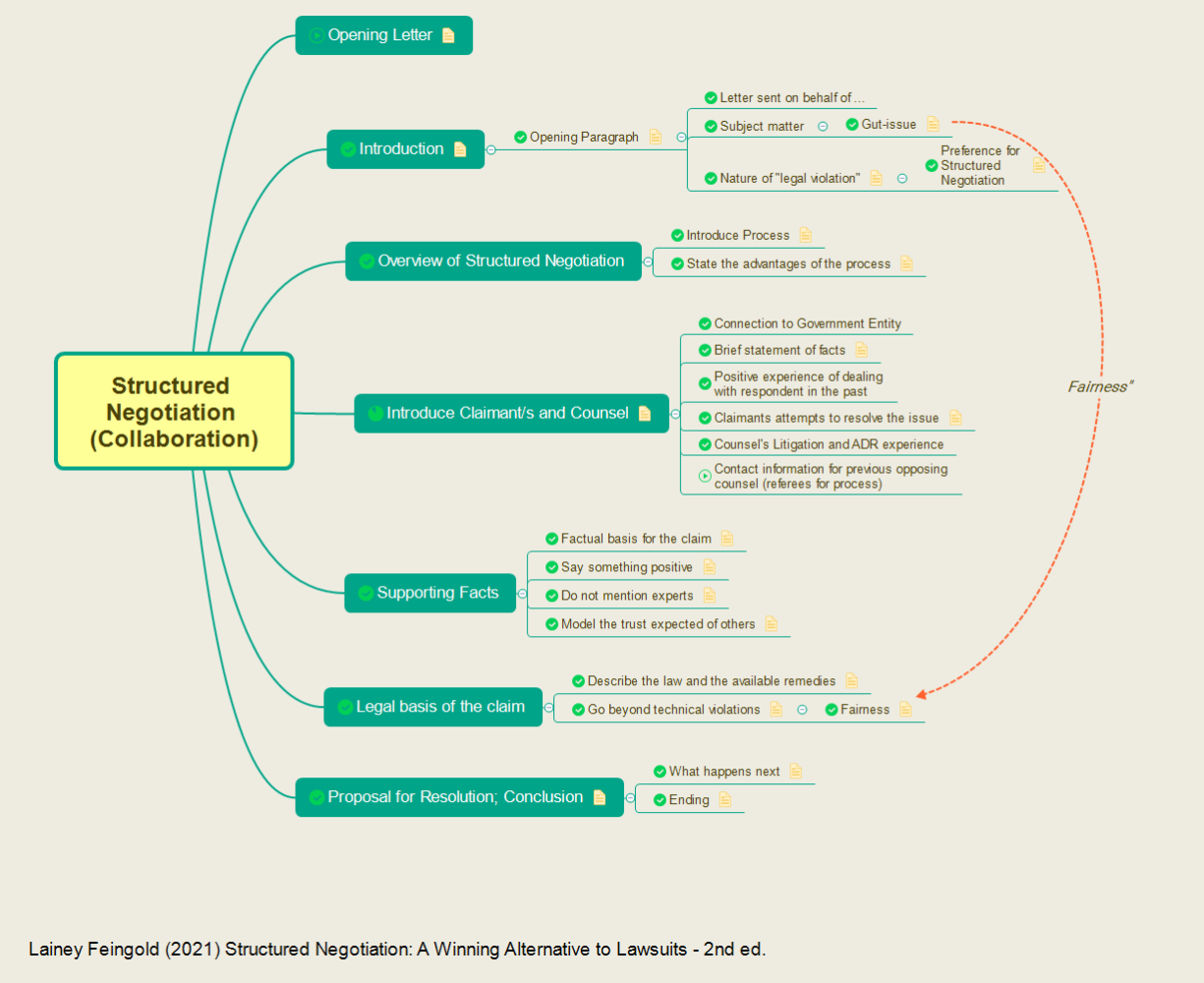

Holding that frame, I then turned the how-to section of Chapter 5, where Feingold describes “the building blocks of the opening letter”. These, she writes, comprise six parts – each of which has a number of sub parts.

I’m not going to take you through a detailed summary of what she says about each part and sub-part. Instead, I’ll offer my mind-mapped version, which I now use as my template when drafting an opening letter. As the map is a .png file, I’ve also uploaded a .pdf version to a LinkedIn post that accompanies this article:

... and appended a text only version at the end of this article.

If you are building your own template, be sure to pay careful attention to the advice that Feingold offers in relation to each part. I’ve incorporated those pieces of advice into each branch of my map so that I can use it a bit like how I would use a recipe that sets out ingredients and instructions. I’ve also included progress icons because I like to see that I am making headway step-by step.

Two Gems

However, I do want to mention two pieces of advice that I found especially helpful though they brought some difficult challenges.

"Model the Trust Expected of Others"

The first piece of advice was to model the trust expected of others. You’ll find it in Building Block #4 Supporting Facts - set out under that heading, where Lainey writes:

Trust is an essential element of the Structured Negotiation process. Without trust all around the table, Structured Negotiation does not work. We manifest trust in the opening letter by being straightforward about the facts and by sharing relevant information. Being forthcoming in the opening letter serves our clients’ interests to build a foundation of trust, cooperation, and good faith. We share what we know to encourage potential negotiating partners to share their information.

In the matter I was working with, modelling trust required me to confront the reality that we had not much prospect of a viable “claim” which would support a cause of action in a case that had already been filed. Faced with that predicament, I could either have bluffed, or I could have chosen to “model trust” by openly acknowledging that reality and indicating that the claimant - as a gesture of goodwill and in a display of trust – would withdraw the current case.

I chose the latter, and explained that this step was not taken lightly but reflected the claimant’s sincere commitment to resolving the matter collaboratively and was taken in hope that a restorative pathway may now be possible.

Take a moment to weigh up what is at stake here.

Every legal instinct might be to fight on in the hope or expectation of forcing a settlement under the pressure of litigation. The claimant might be urging you to do precisely that – and maybe not even in hope of securing a settlement, but out of a deeper need to assert identity, seeking recognition. What, then, is your BATNA (Best Alternative To A Negotiated Agreement/Approach); or perhaps, more realistically, your MLATNA - Most Likely Alternative…? Under that sort of reality testing, what best serves the interests of your claimant?

Some may disagree with the pathway chosen. But once it is determined that Structured Negotiation is the best pathway, then the process will begin to reshape the interests of the parties. That is ultimately what we are looking for – a reshaping that creates safe space for identifying the right thing to do (as between all parties) and for encouraging them to do it.

NOTE: As you reflect on this, it might be helpful to go back and read Chapter 4: Are Claimants Ready for an Alternative Process?

"Go Beyond Technical Violations"

The second piece of advice, set out in Building Block #5: Legal Basis of the Claim was to go beyond technical violations.

If possible, the opening letter should move beyond a technical legal violation.

Our letters presented legal authority, and emphasized the critical need for blind customers to “safely, confidently and confidentially take their medications…”

In our case, this was a matter of necessity, because there was no violation of a legal duty and we had no viable “claim” that would support a cause of action. In reality, we were petitioning for the exercise of a non-statutory executive discretion which, if not exercised favourably, might have been amenable to judicial review in complex and expensive Federal or High Court proceedings.

So, our “gut issue” was fairness. And our opening letter offered – rather than declared – a detailed, values-based fairness framework, which we adapted from the Fairness Triangle as a possible reference point for collaborative reflection. The Fairness Triangle invited us to assess government decision-making in a structured and collaborative way - not solely on the basis of legal sufficiency, but through three interrelated domains: relationship, process, and outcome.

Sometimes you have to stretch in order to go beyond technical violations.

I wanted to mention these two pieces of advice because I think they are related. Without having modelled the trust we expected of our responders, we could not have laid a firm foundation from which we could invite our responders to stretch beyond any legal violation – even assuming there had been one.

Lastly – and almost to complete the frame in which the opening letter is set – Feingold reminds us that:

An opening Structured Negotiation letter ends as it begins, with a tone of friendliness and collaboration, despite the seriousness of the issues raised.

In Closing

Chapter 5 invites more than just a new technique - it calls for a shift in posture. Writing an opening letter in the spirit of Structured Negotiation is not merely about tone or structure; it’s about making the first move in good faith, even when no legal claim compels it. That can be challenging. But it’s also what opens the door to a different kind of resolution - one where trust is not only offered, but reciprocated; where fairness is not merely argued, but explored; and where the right thing, whatever it may turn out to be, is discovered together.

I encourage you to read this chapter carefully. Try out a letter. Choose a case. See where the invitation leads. I’d love to hear your thoughts and see what drafting samples you come up with. And please be sure to indicate if you’d like feedback – either publicly in the comments section or by direct message.

Engage

Serious Invasion of Privacy in Public Housing

R is a long-term resident of public housing. R recently discovered that a senior housing officer had disclosed R’s mental health information to a local tenants’ group without consent. The disclosure occurred via email and referred to R’s relocation request and disclosed confidential details of "difficulties" which R had encountered with the local tenants' group. As a result, R faced stigma, stress, and social isolation.

R wants:

A formal apology from the housing department;

A review of internal protocols;

Financial redress for distress caused;

Assurance that this won’t happen to others.

The housing department has not denied the disclosure but argues that it was unintentional and not a breach of “any enforceable duty.” A court claim would be uncertain, stressful, and expensive. It would expose R again to the trauma of disclosure.

Prompt: Could Structured Negotiation be an alternative? If so, how would you frame your opening letter?

Text Only version of my Mind Map

Structured Negotiation (Collaboration)

1.Opening Letter

2.Introduction

2.1.Opening Paragraph

2.1.1.Letter sent on behalf of ...

2.1.2.Subject matter

2.1.2.1.nbsp;nbsp; ature of legal violation

2.1.3.1.Preference for Structured Negotiation

3. Overview of Structured Negotiation

3.1.Introduce Process

3.2.State the advantages of the process

4.Introduce Claimant/s and Counsel

4.1.Connection to Government Entity

4.2.Brief statement of facts

4.3.Positive experience of dealing with respondent in the past

4.4.Claimants attempts to resolve the issue

4.5.Counsels Litigation and ADR experience

4.6. Contact information for previous opposing counsel (referees for process)

5.Supporting Facts

5.1.Factual basis for the claim

5.2.Say something positive

5.3. Do not mention experts

5.4.Model the trust expected of others

6.Legal basis of the claim

6.1.Describe the law and the available remedies

6.2. Go beyond technical violations

6.2.1.Fairness

7. Proposal for Resolution; Conclusion

7.1.What happens next

7.2. Ending

References

Lainey Feingold (2021) Structured Negotiation: A Winning Alternative to Lawsuits, Second Edition. A11y Books. Kindle Edition.

Sharon Pratchler, K.C., Ombudsman Sasketchewan (2023) Annual Report, pp. 7-8. https://ombudsman.sk.ca/app/uploads/2024/04/2023-Omb-Annual-Report.pdf